We’re on the True North helicopter…

Below us the rain-covered jungle, in which Alan, our pilot, uses an app to find the landing position. In the short term, the True North received clearance for the route from Bougainville’s air traffic control, which the Japanese admiral Yamamoto Isoroku may have chosen for his small squadron on April 18, 1943. Admiral Yamomoto, who triggered America’s entry into World War II with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, remained a dangerous enemy to the United States for as long as he lived. Operation Vengeance (revenge) began after American intelligence was able to decode an encrypted Japanese radio message.

Unlike the Australians, who are more familiar with the history of World War II in the Pacific, I have no particular expectations of the lonely plane wreck lying in the impenetrable hinterland. But the course of our mission should be a memorable experience.

Forty minutes ago we started from our ship, the True North, in clear weather and from the cockpit the pilot Alan and Simon together look for the place where we are expected. Simon made an appointment with the residents of a village two hours away to prepare a small patch near the crash site for our landing. Roads or clearly visible markings cannot be seen in the jungle. The aircraft wreck itself is camouflaged by the vegetation. In addition, heavy rain showers with poor visibility shake our helicopter on the way.

Near the suspected position, we discover a surprisingly large number of people who are already waiting for us. A helicopter does not need windshield wipers itself and for the same reason it blows away all the umbrellas of the bystanders when landing.

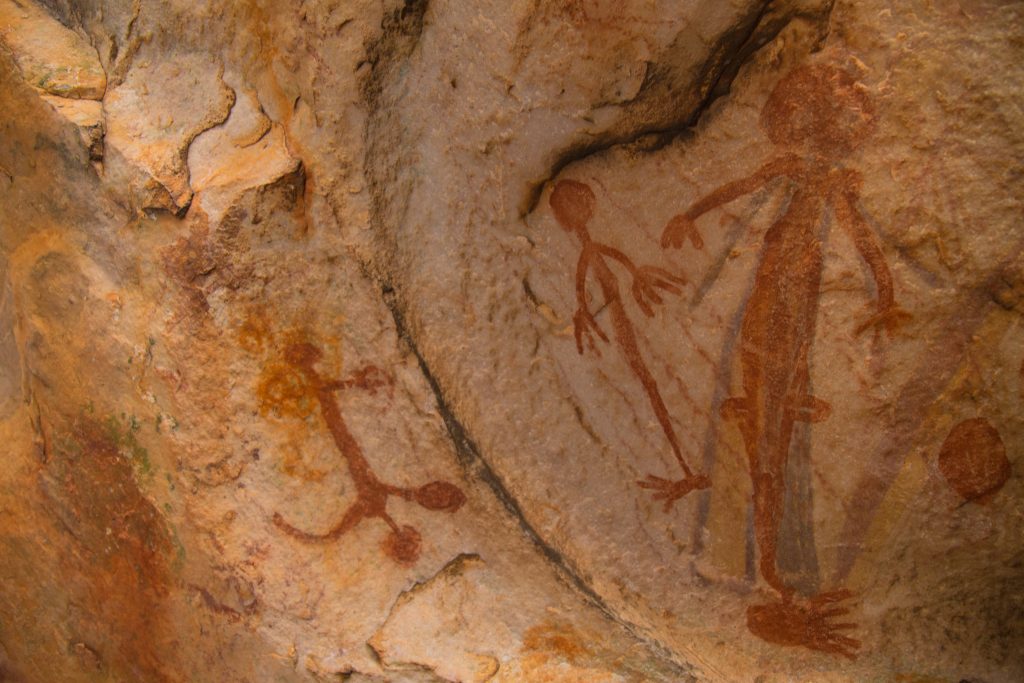

Rarely do strangers make the arduous journey to the prominent plane wreck and nobody has seen another helicopter land here. So the situation is extremely unusual for everyone. I have often had the experience of attracting attention from people who have never seen anyone with white skin. But here the expectations are particularly high and each of our movements is observed in silence.

We are also unsure; not only because the ground is soft from the rain. But people have cleared countless shrubs with their bush knives, the leaves of which, like a mat, prevent you from sinking too deep.

In contrast to the bystanders, who took a full day to witness the spectacle of a helicopter landing, we only came briefly and primarily because of the famous Yamamoto plane wreck.

On the way to the crash site, there are a few opportunities to talk. Even with children you can communicate in English and everyone helps in rough terrain.

The goal has been reached, but it does not want the shudder that I would have associated with the performance of the past drama. Everyday objects like bows and arrows or the bush knives of the bystanders keep me in the present.

Locals try to understand why tourists are particularly interested in the historic plane wreck. Bougainville is currently experiencing the successful end of an ecological revolution. With a large majority, the people decided in a referendum to disengage from Papua New Guinea because they no longer want to be a plaything of foreign powers.

The trip to the plane wreck made me think. Especially afterwards. Because in the situation there was little time to process the many impressions. How much more extreme must our short visit have had on the locals? Who only a few years ago fought with primitive weapons against the armored government army of Papua New Guinea for an intact nature and against a mine that poisoned entire areas. Their lives are deprived but also more contemplative than ours. I imagine that even during the Second World War and at this point, hardly anyone suspected the importance of the event, which is why we made our way here with immense effort.

Today, the people of Bougainville hope that the world’s youngest country will welcome them as kindly as they treat their visitors. Shortly before departure we receive fresh fruit as a gift and can never forget this experience. Also because you would have liked to have had more time for discussions.

Words and images courtesy of Georg Berg.